Fragments and fibres of plastic waste exposed to the environment are already ubiquitous to all levels of the ecosystems and food chains of the Greek seas. This is according to the results of multi-level research conducted by the Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation.

Idyllic Tourist Destination or Open Landfill?

Idyllic Tourist Destination or Open Landfill?

At a time when the Greek and EU authorities constantly refer to aims and strategies for environmental protection (Green Deal, Blue Growth, Green Growth, Integrated Maritime Policy, etc.), Greece – which should be a competitive and idyllic tourist destination – continues to provide the embarrassing picture of open landfills in so many areas, both during the tourist season and the rest of the year. Scattered waste is found everywhere, at sideways of urban and rural roads, in tourist and coastal areas and highly biodiverse ecosystems, but also next to archaeological sites, while most of this culminates in the sea.

Throughout Greece, illegal or inappropriate landfills are dispersed, while several municipalities continue to carry out illegal incineration in their open-air landfill sites. In addition to the heavy impact on the environment and public health, these landfills come with a great cost to Greek taxpayers. Between 2015 and 2018, a staggering 100 million euros worth of fines have been imposed on Greece by the EU, and the fines have continued ever since!

While countries such as Germany, Denmark, Finland, Belgium and the Netherlands manage only 1% of their waste through landfills and Sweden has completely abolished landfilling, Greece insists on maintaining its current negative record in the EU by burying over 80% of its “official” waste. Of course the thousands of tons of waste scattered throughout the environment are not recorded in any statistics and are therefore not taken into account by official waste records. In Greece we consider it a success that we have finally reached recycling rates of 16%. Although, this percentage is mainly due to the exemplary organised recycling efforts carried out by only few municipalities. Also, the unofficial work by specific groups of the population, for example, the Romani (gypsy) community, provides a truly invaluable contribution to recycling.

And if all this is the result of decades of inadequate waste management, now that going plastic free has become a trend for many, it seems citizens and the state once more are losing sight of the bigger picture. We now have to try and solve the problem of plastic pollution with seasonal actions and lifestyle choices. While the latest popular “innovation” is the creation of misleading posters or advertisements of plastic-free destinations referring to islands that do not even have basic waste management.

As if this were not enough, citizens are becoming receivers of an attempt to disorientate them from the real causes and solutions to this problem. For decades, we have allowed the problem of waste management in Greece to swell inconspicuously, squandering national and European funds that could provide for the creation of the necessary infrastructure. Now, some are trying to convince us that by just replacing our plastic straws with biodegradable alternatives and by other such lifestyle choices doing nothing more, we will contribute to solving the problem, even though our whole life is surrounded by disposable plastics.

In fact, foundations, media and companies that have a large financial background as well as direct access to state authorities are joining this game. But, instead of substantially contributing to the solution of the problem with the means that they have at their disposal, they contribute to its perpetuation, ultimately disorienting the citizens as they are solely consumed in communication actions and beach cleaning events.

(Beach cleaning is an action that has been done well for decades by citizens throughout Greece – an action that we all take for granted and everyone should be part of. However, we would expect something more from the aforementioned organisations and companies if they were really interested in this burning issue and did not only care to focus on communication actions).

Research on Plastic Pollution in the Greek Seas

Research on Plastic Pollution in the Greek Seas

Regarding the effects of plastic pollution, Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation alarms citizens and authorities with results based on the multi-disciplinary research it is carrying out for over a decade. This research aims to assess the real extent of the problem, i.e. the dispersal of plastic waste fragments and fibres in our seas and their presence and accumulation in the food chain. The results are extremely worrying. After analysing several thousand samples and publishing 12 scientific papers, we conclude that the fragments and fibres of plastic waste exposed to the environment have already affected all levels of the ecosystems and food chains of our seas.

Indicative Results of the Research

Microplastic Fibres in Marine Species

Microplastic Fibres in Marine Species

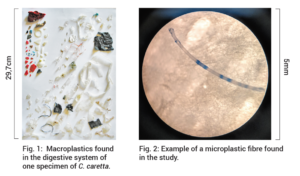

The Archipelagos Institute’s research over the last 3 years has focused on assessing the extent of microplastics in 14 different species of fish and marine invertebrates. Samples were also collected from 46 deceased dolphins, turtles and seabirds, which washed up on various shores of the Aegean. The estimation of microplastics found were isolated exclusively from the digestive system of the aforementioned animals, An indication of the tragic status we have all created is that there was not a single individual sampled, was found with no microplastics inside.

– 3,554 plastic fibres and fragments were found in the digestive system of 18 sea turtles.

– Microplastics were identified in all commercial species of fish and seafood. It is noteworthy that, in a single sample alone, 642 microplastic fibres and plastic fragments were recorded.

However, we must point out that microplastics were only analysed from the contents of the digestive system. Fortunately, this does not mean the fish is inedible, provided the digestive system is removed before cooking, allowing fish to remain a food source of high quality and nutritional value. This however does not apply to marine invertebrates such as the sea urchin, as its entire digestive system is consumed as a delicacy, along with the microplastics found within.

Plastics and Microplastics on Coasts and in the Open Sea

Plastics and Microplastics on Coasts and in the Open Sea

The Archipelagos Institute maintains 7 monitoring stations on various small, inaccessible beaches and coastal areas across two Aegean Islands, where the accumulation rate of plastic pollution is measured. Waste is recorded and collected at least once a week, throughout the year. After 937 recordings over a period of 4 years, there has not been a single day that no new plastic waste was recorded on the shores. Therefore, the claim that citizens are solely responsible for the pollution on the beaches is misleading, as over 95% of the waste that accumulates on the shores is recorded to originate from the continuous and widespread dispersal of waste from the land, and later dispersion by sea currents.

Today, we have the urgent obligation to gain some of the lost time in Greece regarding the issue of waste management and plastic pollution and it is hence imperative to move quickly and efficiently. Waste management can be applied correctly and sustainably, and the knowhow is extensive as it has been practiced for decades in most EU countries. Therefore, there is no need to waste any more valuable time re-inventing the wheel. It has come to a point where we need to stop focusing on frivolous campaigns for biodegradable straws and to proceed with a mobilization at all levels, substantial enough to be able to reverse this tragic scenery in Greece, with the ultimate aim of the environment to become free from every single piece of exposed plastic.

For Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation

Thodoris Tsimpidis

Idyllic Tourist Destination or Open Landfill?

Idyllic Tourist Destination or Open Landfill?

Research on Plastic Pollution in the Greek Seas

Research on Plastic Pollution in the Greek Seas Microplastic Fibres in Marine Species

Microplastic Fibres in Marine Species Plastics and Microplastics on Coasts and in the Open Sea

Plastics and Microplastics on Coasts and in the Open Sea